Victor Stabin Interviews Victor Stabin

VS: When did you become an artist?

VS: I became an artist after I left illustration.

VS: That’s quite the declaration. How so?

VS: Illustrators are like firefighters. A bell rings, you jump in the truck and put out the fire, or in my case, a telephone rings, a client calls wanting imagery, and Vic comes to the rescue. At 46, after 23 years of illustrating for many notable clients*, I found myself sleepwalking through assignments. No matter how exciting the job, my talents were misplaced. It got old, making quality products I no longer cared about. What was I waiting for?

Twenty-five years ago, an oncologist told me there was a tumor over my heart the size of an orange, giving me a 50 / 50 chance of survival. Nothing rhymed more with orange than, before you die, stop illustrating and start painting. I no longer had the head space to wait for a call to get a job. Everything became personal. The only client I needed was my ideas, on my terms.

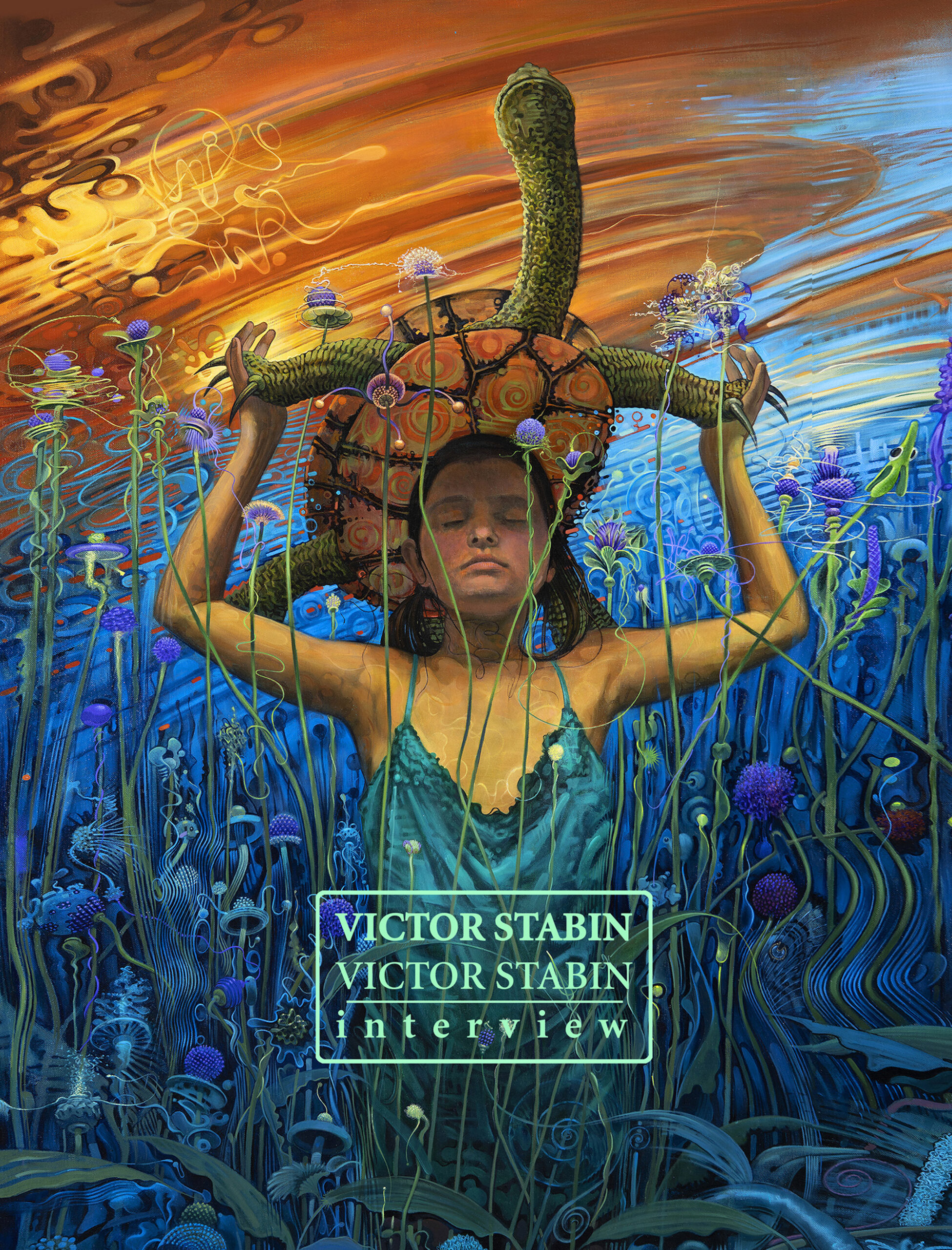

The Hatchlings Oil on linen 48″ x 72″ Title by Dr. Carl Safina

VS: Vic, that’s a pretty pithy answer. Tell us what you did next.

VS: I started with a thematic body of oil paintings. The Turtle Series became a self-imposed assignment. The more I got into the series, the less it seemed like an assignment and more of a passion.

While working on the series, I got married and started a family. Our daughters were high verbal word sponges; it was a gift to be alive and to read to them. ABC books were the go-to. A is for Apple, B is for Apple, C is for Apple, and D is for Apple started turning my brain into puddin’. For my kid’s sake, I aspired to do better. I indulged my ADD at the expense of the Turtle Series and turned to my old friend, the dictionary, to develop ideas for an alliterative ABC book. Daedal Doodle the ABC Book for the Ages, was born.

As all this was happening, we left NYC, reestablished in the small town of Jim Thorpe, PA, bought a 1,600 square-foot 160-year-old factory building, and turned it into the Stabin Museum. Nineteen years into renovations, it’s more than a showcase for forty-five years of my work; it’s expanded into Restaurant Arielle and Vic’s Jazz Loft, with the goals of creating a cultural dynasty, showcasing the stunning talents of my daughters, Skyler Stabin, songwriter and pianist, and Arielle Stabin, painter and image maker extraordinaire.

*New York Times, Time, Newsweek, Cunard Lines, Rolling Stone, KISS, 9 US postage stamps

Fish Ferris Wheel Oil on linen 48″ x 32″

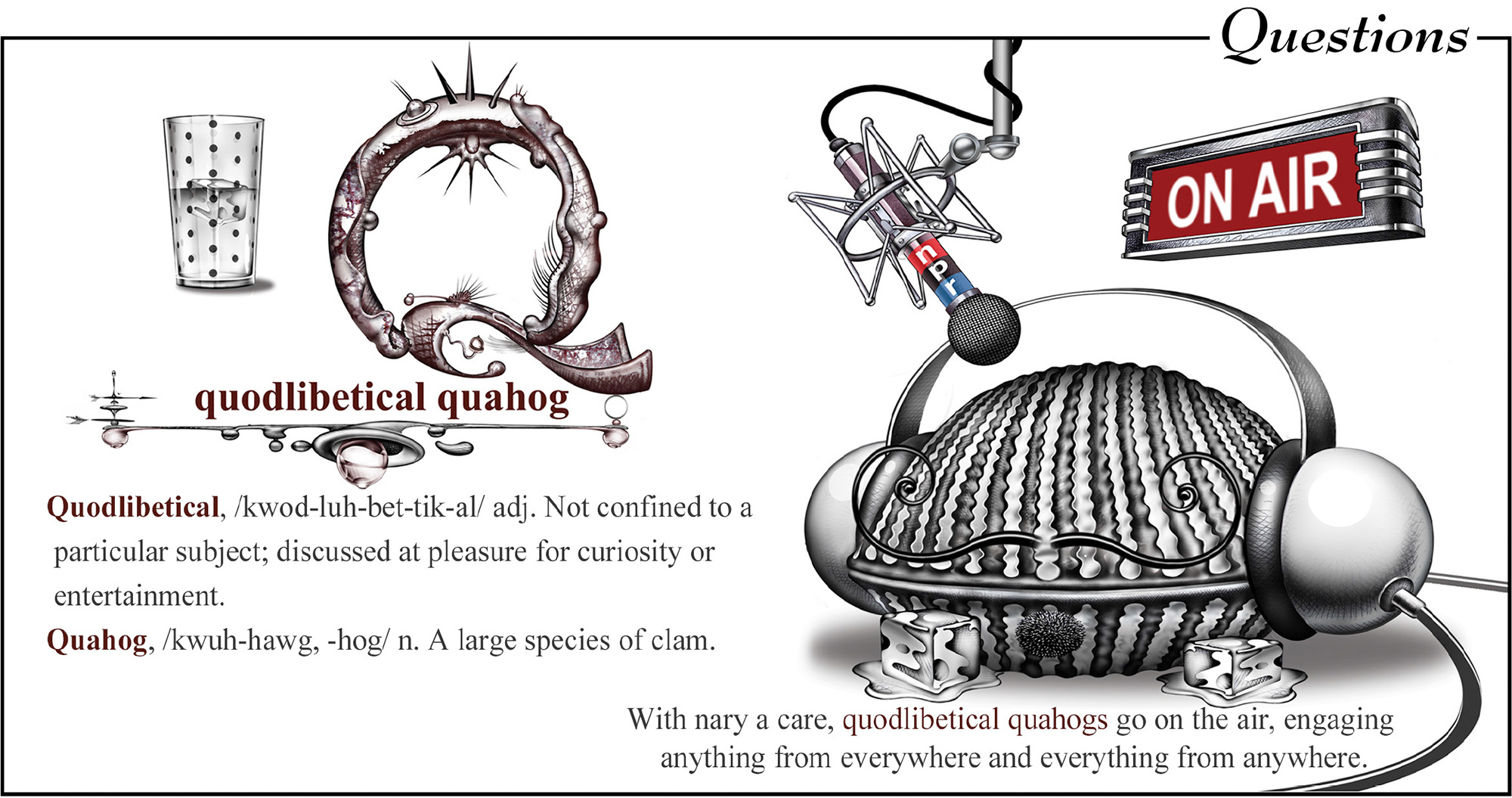

VS: Please take a shot at explaining how the Daedal got its Doodle.

VS: Our book, Daedal Doodle, was created using the dictionary as a map. From it, I learned the power of a single word’s ability to create images. Over a three-and-a-half-year period of reading the dictionary, I culled lists of descriptive words previously unknown and unused by me, one letter section at a time. I read 4,000 pages of dictionaries twice, making lists of words. As I read and reread the lists, ideas came into my head at tremendous velocity. After doing the first three alliterations (A, B, and C), I was hooked. The process was magically creating brilliant images.

Daedal Doodle, the ABC Book for the Ages, has become an unpredictable calling card. For starters, it’s been given a one-person show at the Allentown Art Museum and a lecture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; I’ve taught classes on visual conceptualizing, ranging from 5th graders to college teachers, which led to making a formal educational guide explaining the making of the book; NPR interviews; two award-winning animations voiced by NPR superstars; recently Crayola asked me to be a part of an interactive art museum in Singapore; a comic strip; an invitation to teach at a high school in Uganda; and best of all 600 5th graders are flying me out to Ohio to celebrate the making of 27 student versions of Daedal Doodle books using the Daedal Doodle Dictionary Curriculum Guide. Lastly, Elon is taking Daedal Doodle to Mars and beyond.

VS: Excuse me?

VS: So, viewers constantly asked what are the characters’ stories? I had nothing; I’m not a writer, had no writing intentions, but enough people threw peanuts. Influenced by the brevity of Aesop’s fables, I started to write stories about a page and a half long using the characters from Daedal Doodle. Actually, between us, there’s not enough ADD to go down the path of selling us as a writer; the stories became scripts for animations. The animations take place in NPR radio studios. I sent the scripts to NPR superstars asking for their voices and landed some whales, Dave Davies from Fresh Air and Brook Gladstone from On The Media. The animation E=MC3 has gotten into 14 film festivals.

VS: E=MC3, that’s quite the provocative title. What’s it about?

VS: Well, Vic, it’s about 12 minutes and 8 seconds of storytelling heaven in a style reminiscent of E.L. Doctorow meets Groucho Marks. It’s the true story of how Albert Einstein and his colleague Leo Szilard invented a perpetual motion safety refrigerator that brings peace to the Middle East.

VS: You’ve got to be making this stuff up.

VS: I am not, after all, we are talking about Einstein. And besides, everything I say is true.

VS: What do you think about the animation process?

VS: It allows you to stretch your talents into dialog, editing, storytelling, movement, etc., in service of your imagery. Working collaboratively with the brilliant talents of animators, musicians, sound effects, and sound production experts is the definition of excitement.

VS. So Vic, where can we see this stuff?

VS. Well, Vic, go to Victorstabin.com and click animation on the menu bar.

VS: Tell the folks about our doodling habit.

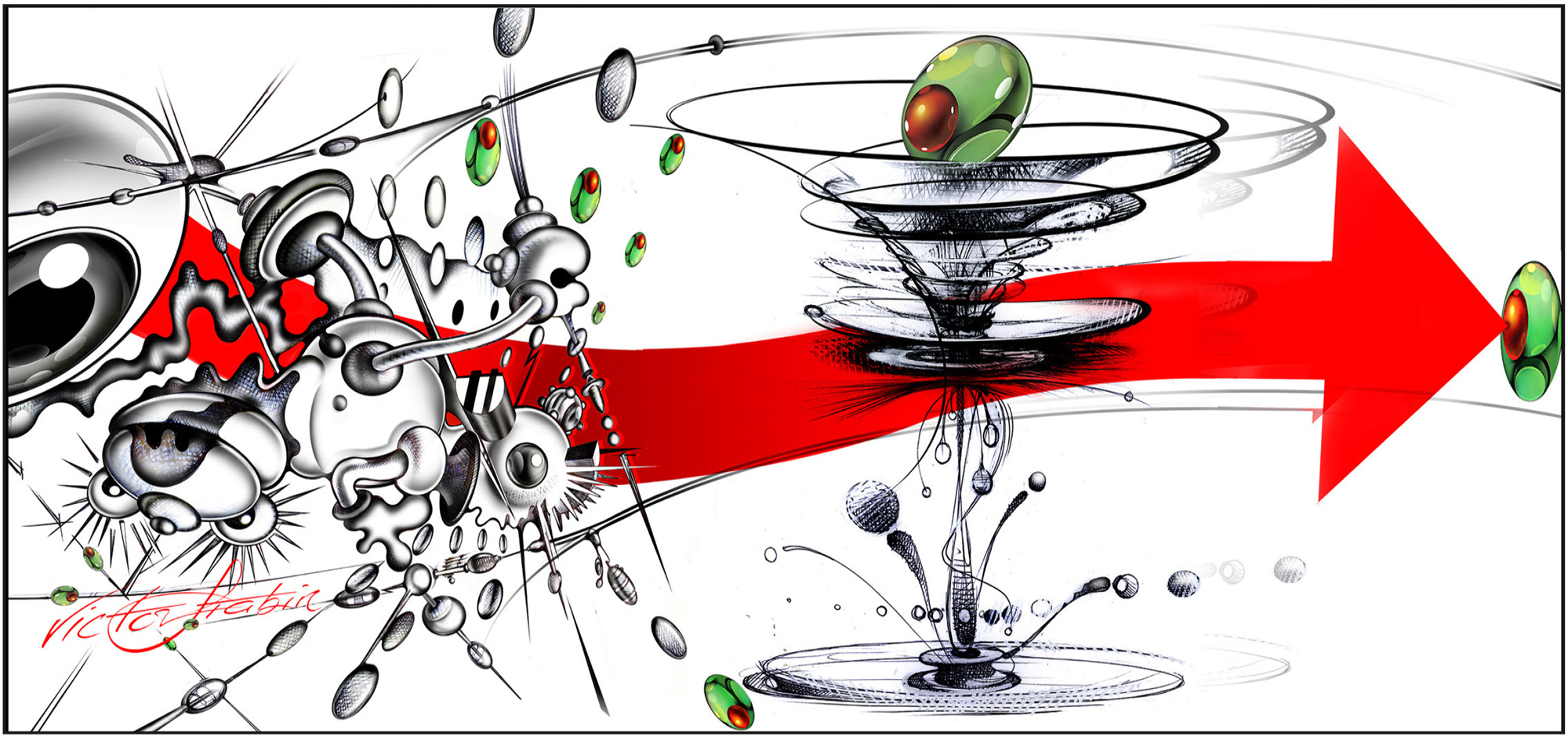

VS: Doodling is my nervous tick; it started in my teenage years. My earliest memory of drawing that relied on inventive doodling was of Victor Moscoso’s zany black-and-white illustrations in ZAP Comics. I have a passport-size wallet stuffed with 3X5 index cards. If I’m sitting and waiting, it’s doodle time. Some of the drawings are quite fetching; the good ones get rendered in Photoshop, taking it to a doodle strata of high low-brow doodling (hence the generously displayed elaborate arrow doodle). A calligraphic line quality developed while doodling made its way into my painting, creating a signature brush style. When you lean into my work, you’ll see it everywhere.

VS: And the origins of the Turtle Series?

VS: Chemotherapy treatments wreaked havoc on my body and mind. The medicine that poisoned the fast-growing cancer cells also reduced oxygen to the brain. The resulting ups and downs of chemo and steroids created a foggy haze called chemo brain.

For distraction, I turned to my guitar and repeatedly slammed “Three Chords That I Like,” a harsh song (I wrote) with five words and three chords. The repetitive chant created a catalyst for my painting series. Three cords became three things that I liked, and became the foundation for the series.

-

- The first and favorite element I wanted to include was the soft mitigating edges created by sea grass as it leaves the water and meets the land, as it does in my favorite spot on Fire Island’s magical moonlit Great South Bay, where I had summered for ten years.

- The ellipse is my favorite shape. Elliptical orbits lineate the universe, and in my humble opinion, are the only way to travel.

- While snorkeling in the Caribbean, I encountered a sea turtle and tried to catch it. The creature allowed me to get as close as a couple of inches away but never close enough to touch. We swam in tandem for half an hour until, mystically, the deity abruptly vanished off into the distance. I was awed by the playful intelligence and humbled by its dominance of the environment, hypnotized by graceful moves, dazzled by its beauty, and stunned by my ignorance.

Years later, I saw a painting by René Magritte, Le Joueur Secret (The Secret Garden – 1927), portraying a leatherback turtle floating above a cricket match. Soon after seeing the Magritte painting, while walking past the Barnes and Noble bookstore on Astor Place in NYC, I spotted a poster by Marshall Arisman, my professor at the School of Visual Arts and favorite human being. It was a stunning image of a man’s head exploding into a bright yellow aura as a turtle floated past him. The combination of the two paintings put me on the path.

A couple of years in, wondering why I was so comfortable having these creatures tell my stories, I found E.O. Wilson’s book, Biophilia Hypothesis, it offered a compelling explanation of the natural bond between humans and other living creatures. Wilson contended that humans have coexisted intimately with animals until as recently as 200 years ago, before the industrial revolution. We evolved as creatures deeply enmeshed with the intricacies of nature and still have this affinity ingrained in our genotype today. Wilson supported his theory with stories that appeared more like fables than reality. The stories are a bridge to the ineffable connections to the natural world.

With the births of my kids, the paintings became autobiographical allegories. The Turtle Series has created the most natural and personal connection I’ve yet to have with my work. Painting my family in the context of this mythically ancestral creature is as intuitive as breathing.

Lifespan aside, the paintings make me immortal. These are my stories. The more of this work I do, the longer I live.

VS: Amen. Vic, that’s pretty much the way I remember it as well. Moving on, what are your influences?

VS: The Surrealists from Bosch to Dali, MC Escher, Dr. Suess, the obsequious smiling of 20th-century advertising art*, 19th-century Japanese watercolor print artists, the doodles of Victor Moscoso, Vincent Van Gogh, the Italian Renaissance’s spirit of technical excellence, the boundless reaches of modern art, just about anything I lay my eyes on, and the fragility of life.

VS: Vic, 268; what is the significance of these numbers?

VS: 268 West Broadway changed the course of my life. My wife, Joan, had a getaway place in Jim Thorpe, PA. We went there every weekend to the point that we just moved. After 48 years of living in NYC, I decided to try something different and breathe clean air. We weren’t definite on Jim Thorpe, but while here, I rented a 2000-square-foot studio space in a 16,000-square-foot building. A year later, it came up for sale. It was dilapidated, but artists need old buildings. We’ve been fixing it up for 19 years. Before electric motors, 268 was built over water for hydro-power—the building’s first factory made braided steel cables for suspension bridges, including the Brooklyn Bridge. As we repurposed this 160-year-old for the fifth time, we’ve exposed the waterway under the restaurant, with future plans to do the same in the main gallery. 268 is often compared to (but never confused with) Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Water. It’s the home of the eponymously named Stabin Museum, Restaurant Arielle, Vic’s Jazz Loft, my studio, plus an Airbnb for luminaries. I dream of 268 becoming a home for my daughters’ talents. Passionately being rebuilt, 268 West Broadway is a must-see destination.

VS: Well, Vic, I think we’re good for now. Is there anything you’d like to finish with? Perhaps a favorite quote, something with a bit of pith.

VS: Here’s one from Michaelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni “Lord, grant that I may always desire more than I can accomplish.”

VS: Thank you, Vic. It’s been a delight talking to us.

VS: Ditto

VS. PS Vic, Why do you call yourself an Eco-Surrealistic Alliterator?

VS. Have you read the interview?

The image started as a stick figure on a 3 X 5 index card. I keep a small stack of cards in my wallet for doodles. Doodling is my twitch, the itch I love to scratch. My brother, Michael, lives in a psychiatric ward at Creedmoor State Hospital in Queens, New York. He suffers from schizophrenia. I visit him when I can, sadly his day-to-day is limited, leaving him little to talk about. The facility does not allow cell phones, so I can’t show him family pictures or surf the web. Books and Chinese food are permitted (Chinese food is his solitary request). His mind has been incarcerated since he was 17 years old. He’s now 63. As noted, this condition often afflicts brilliant minds. One of the things I can do with him is show him my doodles. Sometimes, the drawings are no more than spindly stick figures. He’s creatively concise and fast with descriptions. This time he came up with a knockout – “The All Seeing Unfeeling Eye.” His title excited me enough to spend a week rendering the sketch. The act of writing this is making it evident to me; I should take a stack of favorite doodles, have him title them, take the best ten, and turn them into a series-working title “Creedmoor Psychiatric.”

The Birth of an Image

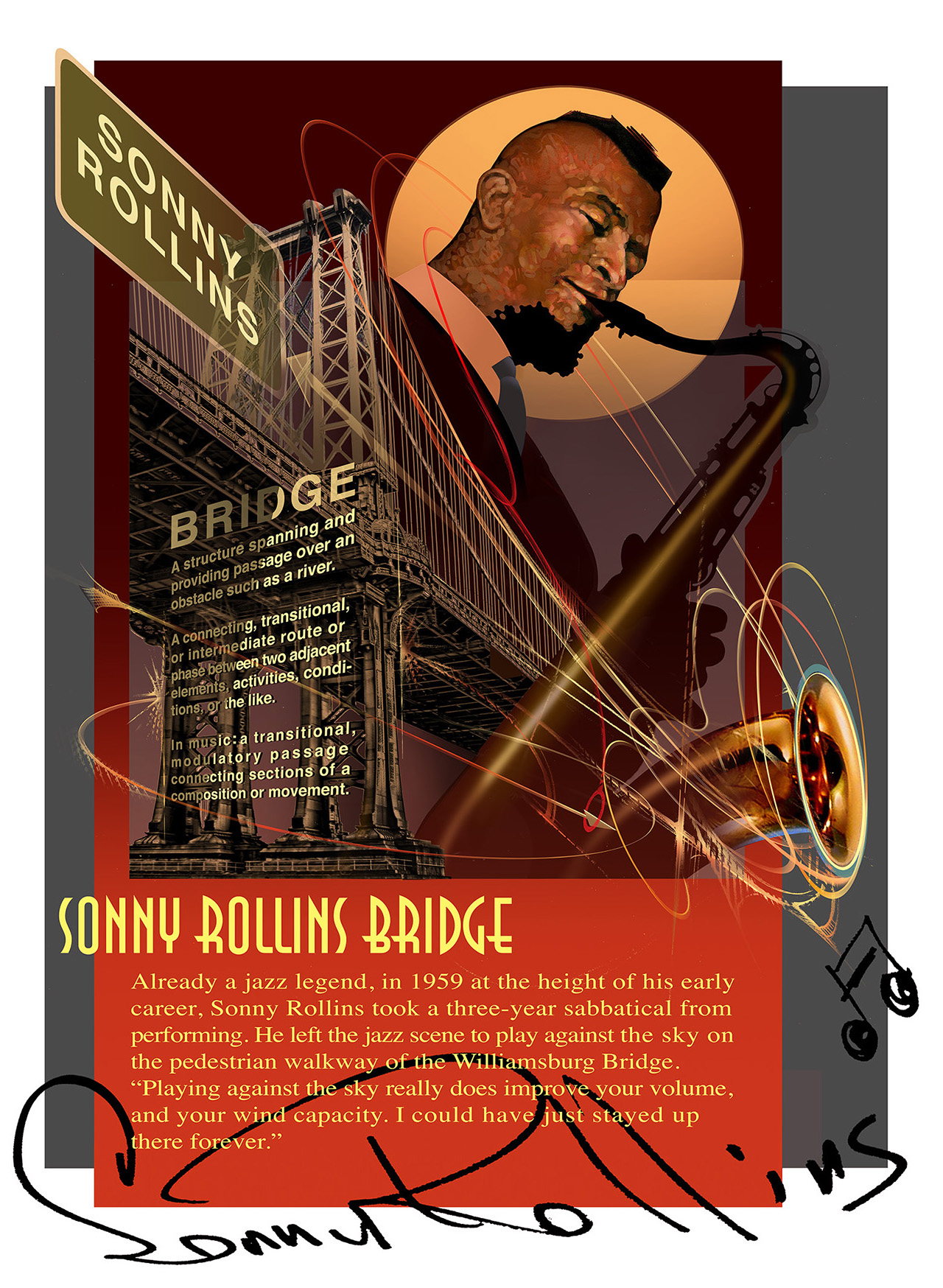

In October 2017, I was listening to The Brian Lehrer Show on public radio station WNYC. Brian was speaking to a man named Jeff Caltabiano about his campaign to rename the Williamsburg Bridge after jazz saxophonist Sonny Rollins – the Sonny Rollins Bridge. Joining Caltabiano was comedian Negin Farsad and jazz musician, Clifton Anderson, who is Sonny’s nephew. Farsad admitted to not being a jazz fan, but she had actually co-directed a short documentary about Sonny and the bridge.

Caltabiano wanted to rename the bridge to honor the time from 1959 to 1961, when Sonny had stepped away from the jazz scene. During that time, he would go to the Williamsburg Bridge and play for 16 hours a day. 1959 was an amazing year in jazz – I mean, Miles Davis released “Kind of Blue,” John Coltrane dropped “Giant Steps,” Dave Brubeck hit us with “Take Five.” There was also new music from Art Blakey, Charles Mingus, and Ornette Coleman. A whole lot was going on, and then you had Sonny walking away. He was 28 years old. I’ve spent a lot of time listening to Sonny’s music, and I feel the way Coltrane felt about him. When asked who he listened to when he wanted to hear saxophone, Coltrane replied, “Sonny Rollins.” About his time playing on the bridge, Sonny told the New York Times “Playing against the sky really does improve your volume, and your wind capacity. I could’ve stayed up there forever. But Lucille (his wife) was supporting us, and I had to go back to work. You can’t be in heaven and on earth at the same time.”

One of the first things I noticed when I went to Italy, is that the Euro notes there show images of Italian culture, celebrating artists like Michelangelo, Raphael, Da Vinci, Caravaggio, Bernini, and the composer, Bellini. If the Williamsburg Bridge were to be renamed after Sonny Rollins, not only would it be the first bridge in New York to be named after an African American, but it would also be the first named after a cultural figure, and not a political one. I’m from Brooklyn. Before moving to Jim Thorpe, PA in 2002, I spent my first 48 years in New Stabin / Birth of an Image / 2

York. Since I’ve left, the city has been changing the names of bridges and highways celebrating politicians. In 2011, the Queensboro Bridge (also known as the 59th Street Bridge) was renamed the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge. I remember Mayor Koch in the 1980s – he balanced the city budget, implemented the Pooper Scooper Law and fought unglamorous battles with Black community leaders. Upon hearing about the renaming of that bridge, I immediately thought it should’ve been renamed the Paul Simon Bridge. When he was 23, Simon wrote “The 59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin’ Groovy).” He’s an American original, a national treasure, a nice Jewish boy from Queens, New York. If he had been born in Italy, “Paolo” Simon probably would’ve had a city renamed after him (or, perhaps he would’ve gotten his image on a coin). I would later find out that the Williamsburg Bridge had been named after Benjamin Franklin’s grandnephew, Colonel Jonathan Williams.

The Brian Lehrer segment inspired me to offer my talents as an artist to the renaming project. You see, I felt as though I needed to change the Williamsburg Bridge into the Sonny Rollins Bridge. I also felt that if I didn’t create a piece of the bridge coming out of Sonny’s mohawk, I would be persona non grata. That’s my life as an artist. I don’t create because I want to, I create because I have to. I knew what the Sonny Rollins Bridge looked like, and I was constructing it with my very own hands.

Naturally, I wanted Sonny to see my work. Rumor had it that he was living in Woodstock, NY. I called the Woodstock postmaster. He told me that 10,000 people live in Woodstock. He wasn’t personally familiar with Mr. Rollins, but he was confident that his carriers would know whether or not he lived there. He assured me that he would return the posters to me if Sonny didn’t live there. To prove that he could be trusted, he told me that that they had just returned a letter that was sent to Janis Joplin.

Sonny received the posters and he was kind enough to sign copies for me. I lifted his signature off the prints and then added them into the two posters. Wow! After that, I loved him, as well as his music, and it made me happy that I could help him to stay up on the bridge forever.

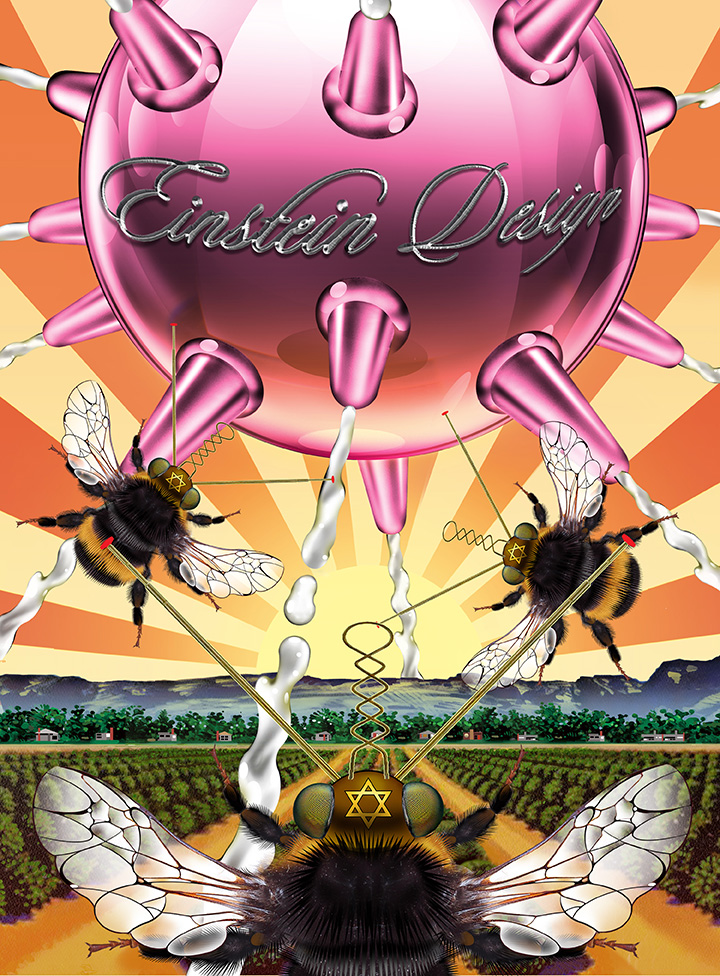

Hand on the Bible, in Berlin, circa1922, Leo Szilard (the father of the Nuclear Reactor) and Albert Einstein (the mind that organized the universe) truthfully did patent a safety refrigerator. The image above and below images from E=MC3 are used when describing the Atomic Age & The Land of Milk and Honey, in my upcoming animation titled E=MC3.

The animated allegoric sequence starts with an atom looming over a meadow and ends with a flying udder nourishing the landscape with milk, as radio-controlled jew-bees pollinate an orchard, before heading for the hive to make honey. The red text is from the animations script.

Szilard never looked back and went on to create the patent for the nuclear reactor, ipso facto jump-starting the Atomic Age. Einstein got sick of having his life bifurcated by appliances and physics and frankly did not want to duke it out with GE and Westinghouse. In agreement with Einstein’s wishes, Israel will also be using the Kitchen Appliance patents-accrued gelt*, to bring stability to the Middle East and once and for all turn it into the Land of Milk and Honey, as promised in the Bible.

*Gelt: Yiddish for money.

stabinmuseum.com 570-325-5588 ◼︎ 268 W. Broadway, Jim Thorpe, PA 18229